The impending buy-to-let boom

This trick could cut your home remodeling costs in half

November 12, 2018Should you use a cash-out refinance to pay off a HELOC or home equity loan?

November 13, 2018Buy-to-let mortgages have helped to transform the concept of housing in the UK over the last few decades. They represent one method by which rental housing can be transformed into an investable asset class.

Now, according to a research note from Integer Advisors, these kinds of loans are beginning to spread into “frontier” markets in Europe — specifically, Ireland and the Netherlands.

Buy-to-let (BTL) mortgages blend some of the characteristics of commercial real estate lending — especially the use of rental income in underwriting the loan — with the borrower type usually associated with residential property (ie, normal people).

In the UK, the loans are often securitised, allowing international investors to gain exposure to incomes that are ultimately derived from tenants, and giving those investors an interest in the possibility of new markets, and incomes, opening up. Just as residential mortgage securitisation allowed investors to gain exposure to home ownership, buy-to-let gives them exposure to renting.

The chart below captures the scale of rental markets in Europe (it does not reflect housing benefits which contribute to rent payments, as opposed to policies which subsidise the price), which are in some cases close to or larger than mortgaged owner-occupied stock, but generally less integrated into international financial markets:

Buy-to-let fosters the emergence of a granular class of landlords, as opposed to the models of larger-scale institutional landlords already present in some countries (and partially provided for by governments).

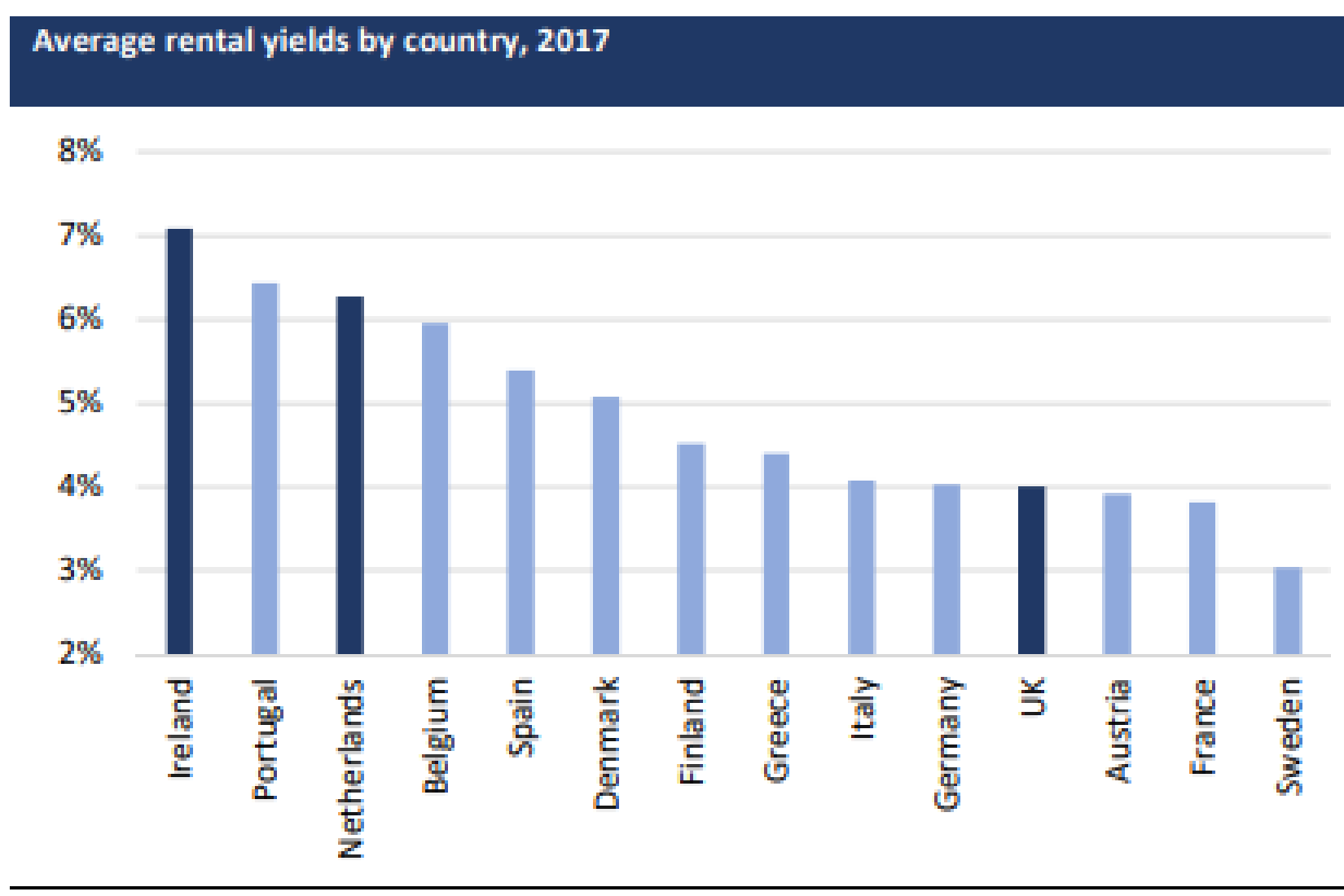

The underlying effect is the deployment of capital to supplement the income of savers, often for retirement. The rental yield in many European countries is significantly higher than what most of the bond market can offer, though:

Source: WorldFirst 2017. Note current yields may be different given the extent of house and rent price changes in the past year

Source: WorldFirst 2017. Note current yields may be different given the extent of house and rent price changes in the past year

There has been an increase in non-bank real estate exposure in general after the crisis. In the US, private equity groups such as Blackstone dramatically expanded into real estate. This has often been driven by institutional investors frustrated by the lack of returns in conventional bond markets in an age of low interest rates and quantitative easing. Private equity has also gained exposure to real estate via purchases of portfolios of non-performing loans, and the platforms which service those loans, as in Spain and Ireland.

Integer Advisors points out that the “contemporary specialist lender constituencies in these newer BTL markets are mostly owned by alternative/private equity investors”.

In Ireland, there has been a “notable” footprint of non-bank specialist mortgage lenders, such as Dilosk and Pepper Money. In the Netherlands, non-banks have ramped up their lending in the residential mortgage market. While the Dutch buy-to-let market is still at an “embryonic stage” — lending is at most €1bn a year — Integer Advisors estimates that non-banks own up to 50 per cent of new lending in the sector.

If this is where the lending might come from, why would normal people decide to invest? Some savers might want to seek out buy-to-let mortgages to supplement their incomes, but others might find themselves involved by accident. There are now around 175,000 BTL landlords in Ireland. Integer suggests that many of these are “accidental landlords”, who previously had residential mortgages but were unable to sell the property when they moved.

It may be easier, in general, to refinance into a buy-to-let mortgage because the constraints are on rental income, rather than a gross multiple of the borrower salary. If there are crashes in residential real estate, one possibility is a subsequent expansion in the use of buy-to-let as a refinancing-tool-of-last-resort.

Another legacy of the crisis is a general rise in renting. Around 30 per cent of households in Ireland now rent rather than own. A decade ago, this ratio was below 22 per cent. As Integer report:

The long-term trend in this respect highlights an interesting pattern — the share of households renting fell perceptibly over the multi-decade postwar period, reaching a low of 18% in 1990 before increasing steadily again.

The Dutch case ties in to “extraordinary structural shifts” over recent years that has “fuelled a demand squeeze”. It also relates to the role of the state in the current distribution of housing ownership:

Legislative changes in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis designed to reduce the dominance of social housing associations, which included for example tighter means-testing for tenants, had the effect of forcing higher income dwellers into the private rented market. There are 2.3m rented dwellings in the Netherlands according to official statistics, but some 80% of this stock is (still) owned by social housing associations, the highest such ratio in Europe. All that aside, the Dutch population is growing at its fastest pace in over 15 years

Buy-to-let is at the intersection of several trends. One is the need to reinvent housing as a financial commodity in the absence of sustainable systems for saving (the UK buy-to-let boom has clearly related to the need to supplement retirement income). The other is competition between new kinds of lenders, seeking out new kinds of borrowers away from the domain of banks. The third is an increase in the proportion of people renting.

All of this could easily be confounded by political responses, as recent tax policies for UK buy-to-let make clear. But it is at least worth noting that the generational, social and financial factors at the heart of the UK’s buy-to-let market have their echoes across Europe.

Related Links:

Non-banks shake up Dutch mortgages — FT

Irish pension funds push into mortgage lending — FT

Spanish bad debt comes good for US private equity — FT